I’ve written an article about Borley Rectory in the most-recent Yuletide Hauntings (Dec 2023) edition of the wonderful Hellebore magazine (there are some great other articles in the edition, so do check it out!).

Unfortunately, the spirits of that cursed residence must have decided to interfere in the design and printing process and cut out a chunk of text at the top of p.91 of the piece. In case anyone was confused, below (well, hopefully, unless the Rev. Bull has been at it again…) is the full text of the article, along with a few of my photos of Borley village.

*

Dubbed “The Most Haunted House in England”, Borley Rectory has captivated the popular imagination since it rose to fame in the 1920s, at the heyday of ghost hunting. Edward Parnell, the author of Ghostland, journeys to the place where it once stood, remembering tales of ghostly nuns, phantom coaches, and otherworldly messages, pondering the weight of formative childhood books, and peeling back the layers of its haunted history.

Its name has troubled me for nearly as long as I can remember. Since I first read about it in a favourite childhood book some four decades ago. There it was, staring out of the pages, complete with coloured illustrations and even a floorplan.

The most haunted house in the world?

And in that formative moment I was certain it must be, despite the presence of the futile question mark that attempted to cast doubt on the grandiose claim which, already, had me hooked.

Borley

A name that should cause the heart rate of any similarly afflicted survivor (like myself) of the “haunted generation” to pick up its pace or to surrender the odd beat. Did the sound of the word, I wonder now, add to its allure? Evoking, perhaps, unhappy bawling spirits, or teenage offenders imprisoned in soul-beating borstals? Certainly, it was anything but boring.

Borley Rectory

Here it is in front of me once again, in my now-battered copy of the Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World: two double-page spreads detailing the peculiar goings-on that plagued the Rectory from its mid-Victorian construction to its fire-stoked end on a February evening in 1939. Four pages to precis a convoluted seventy-five-year saga that’s filled numerous full-length books, as well as several films and television programmes. Among them, the first volume dedicated to the eponymous religious residence of the nondescript Essex hamlet: The Most Haunted House in England: Ten Years’ Investigation of Borley Rectory (1940), written by England’s foremost self-styled “ghost-hunter” of the opening half of the 20th century, Harry Price.

Bewitched by Borley, Price wrote a follow-up in 1946. The End of Borley Rectory was to be his final book (though he was working on a third on the subject), a heart attack less than eighteen months later, during the afternoon of Easter Monday 1948, offering him passage – should such a realm exist – to the spirit world. Ten years on, the so-called Borley Report, a sceptical hatchet job on Price’s investigations by Eric Dingwall, Mollie Goldney and Trevor Hall was published as The Haunting of Borley Rectory (1956). Still, Price’s reputation was at least somewhat rehabilitated over the following decades, with The Ghosts of Borley by Paul Tabori and Peter Underwood coming out in 1973, the same year the Reader’s Digest influential Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain devoted an exaggerated two-page panel to the tale.

Even now, almost a century on from its haunted heyday, new Borley books continue to come. The most recent to date is Sean O’Connor’s comprehensive 2022 review, another The Haunting of Borley Rectory, catchily subtitled The Story of a Ghost Story. O’Connor’s own obsession with the subject was fostered by another children’s classic of the supernatural, in his case The Hamlyn Book of Ghosts in Fact and Fiction (1978), whose garish cover depicts Borley’s flame-filled finale – complete with ghostly figures at an upper-floor window – loomed over by a terrifying gaping-mouthed, blank-eyed apparition and the bewildered nightdress-wearing victim at the heart of the happenings. No wonder O’Connor, and a whole generation, were captivated.

*

With so much written about Borley, you’d think it’d be easy to pin down what may, or may not, have taken place. But it’s slippery and ambiguous. As, I suppose, any good ghost story should be.

For those not aware of the history of this haunted hamlet, here are the bare bones.

Built opposite the church and completed in 1863, the sprawling rectory was commissioned by the Reverend Henry Bull. It was an ordinary-looking – many say ugly, though I think that’s a little unfair – red-brick Victorian country dwelling, softened by a veranda overlooking the tennis lawn that spanned the space between the bay windows of the drawing and dining rooms; the distinctive eastern façade is recreated on the cover of my book Ghostland, so I feel I know it well. The unusual layout included a dreary internal courtyard, a small private chapel, extensive cellars, and various ill-lit corridors that connected the numerous rooms (around twenty-three, depending on how you count them).

Things were unpromising from the start: the death of a 17-year-old labourer, John Whyard – who drowned in the local river during the house’s construction – setting the tone for what was to come, and causing mutterings among the superstitious locals about bad omens.

Classic English haunting tropes soon became associated with the new Rectory: a ghostly horse-drawn coach driven by two headless men was sighted by Harry Foyster Bull, the most-recent Rector (son of the house’s previous incumbent); the grounds were allegedly the site of an ancient plague pit; and, in July 1900, four of Harry’s sisters claimed to have together witnessed the figure of a nun walking through the garden in the gloaming, a tale that would become etched into Bull family folklore and oft-repeated over the next fifty years.

Supernatural phenomena began to really ramp up, however, with the arrival of Eric Smith, an Anglo-Catholic from India who took over religious duties in 1928, following the death of the Reverend Harry Bull in the previous year. (Soon, Harry’s own restless spirit would be said to walk the house’s corridors.) Arriving as outsiders in a place accustomed to decades of the same family tending to their spiritual needs, the isolated rural parish must have come as something of a shock to Eric and his wife, Mabel. The by now rather outdated and difficult-to-upkeep Rectory would not have helped matters: cold, damp, rat-infested and without electricity, the mansion seemed perfect for a ghost or two. During their first days of residence, Mabel found the skull of a woman among a pile of rubbish in the library, which can’t have settled her nerves. Before long, peculiar noises, mysterious lights, moved objects and even the possible manifestation, once again, of the spectral nun had all occurred.

In desperation, the Smiths wrote to their daily newspaper, the Mirror, for advice, keen to have the Rectory investigated by a respected psychical research organisation. What they were to unleash was a tabloid furore – with hundreds of drunken sightseers descending on the grounds of the house, desperate for a glimpse of the nun or the ghostly carriage – and, crucially, the introduction into this strange narrative of ghost-hunter extraordinaire, Harry Price. A charismatic, self-made “psychic detective” who started off as a travelling salesman and would later drive a Rolls-Royce, Price was to become one of the two central figures in the Borley story – a story which was to dominate the next two decades of his life, and to cause endless controversy after his death.

The Smiths did not last long in the dank, dated house, replaced in the summer of 1930 by another expat couple, this time arriving from Canada: the 52-year-old Reverend Lionel Foyster (a cousin of the Bulls) and his glamourous, soon to be notorious, 31-year-old wife, Marianne. With the entrance onto the stage of the Foysters, poltergeistic activities in the Rectory spiked (as did extra-marital affairs and things that go bump in the night of a different nature) – with increasingly violent episodes directed at Marianne, and mysterious scribbled messages appearing on the walls that surely were to provide inspiration for Shirley Jackson’s 1959 horror masterpiece The Haunting of Hill House.

marianne please help get

A brief reference in the fourth chapter of her US-set novel demonstrates Jackson’s knowledge of the Essex events, when Dr. John Montague – something of a Harry Price figure – states: “The cold spot in Borley Rectory only dropped eleven degrees”. Among a number of other similarities, both houses also shared a Blue Room: the protagonist Eleanor’s bedroom in Hill House and the Rectory’s most notorious space in (un)real life.

*

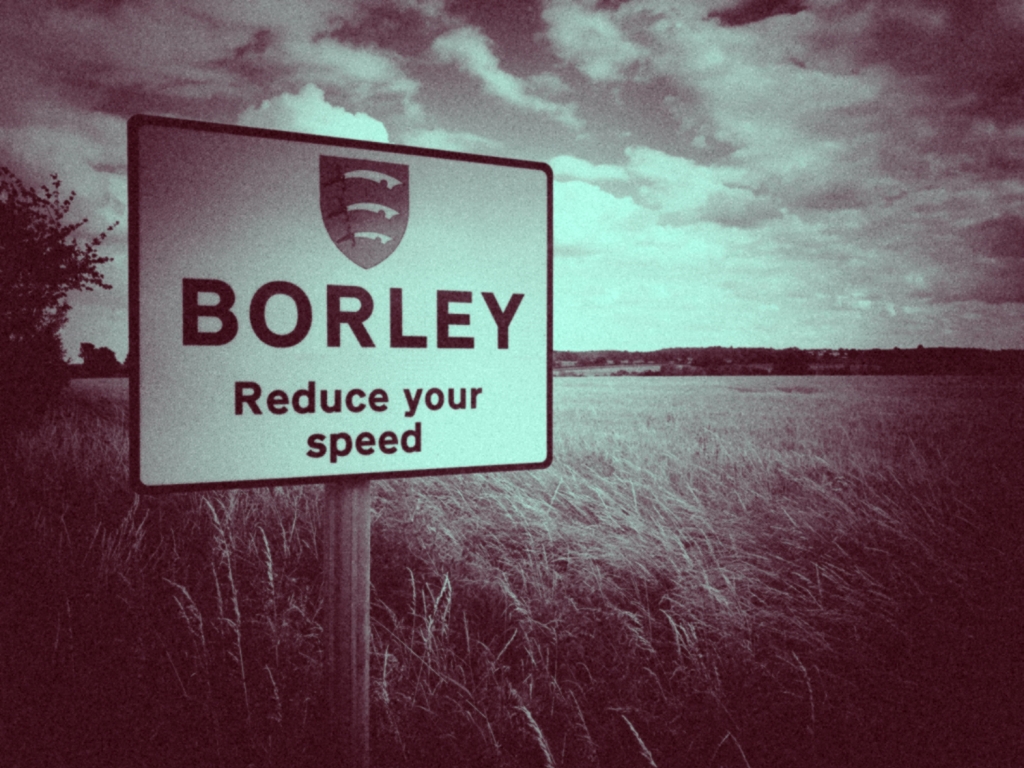

It’s a luminous July afternoon as I negotiate my car along the winding lanes that lead from Foxearth past countless ripening cereal fields. Dog-legging back on itself, the road rises gently from the floodplain of the River Stour. Beneath a red shield bearing three notched cutlasses – the flag of Essex – reads the village sign.

BORLEY

Reduce Your Speed

An avenue of trees obscures the view to the north; opposite are various smartly kept bungalows, with well-tended lawns and white-painted picket fences.

And now, before me stands the church. Across the tarmac, half-hidden by a wall and overgrown hedge, is the red-brick Rectory Cottage. Constructed of similar materials, it’s a building that was already here when Henry Bull built his new Victorian home, and which used to abut the Rectory; I’ve seen an old photo taken from the church tower showing how the two houses once crowded against each other at an awkward angle. Indeed, in 1937 one of Harry Price’s investigative helpers, Major Douglas-Home, noted how: “Owing to the shape of the courtyard & the position of cottage, every sound made at cottage was magnified at least 5 times in the main house.”

I pull into the small parking area and turn off my car’s engine. Those same fields I earlier passed now fall away down the slope in a panoramic vista of yellowed wheat, swaying trees, and occasional half-hidden buildings. On a dead-straight path that leads through a large corn field is a distant, silhouetted figure.

Man, woman, or perhaps scarecrow. I can’t be sure.

It’s strange it has taken me so long to visit. Not, I think, because of any trepidation on my part: I’ve always been more Scully than Mulder. No, more because the village seems so very far off the beaten track, tucked away on this Essex-Suffolk boundary so that you have to be making a concerted effort to get here; the City of London lies seventy miles to the southwest by road and although there is a working station in the nearby market town of Sudbury, its trains run only to Marks Tey outside Colchester.

A real house on the borderland (only without William Hope Hodgson’s otherworldly swine-creatures).

Now I am finally here there’s the question of what to do… I’d attempted, through a friend, to make contact with the warden of the church, but he’d had no response despite earlier successful correspondence. I’ll have to trust my luck, though I’m not hopeful. I step along the block-paved avenue than runs tangentially to the church, each side guarded by unkempt cone-shaped yews. It’s a little claustrophobic, but perhaps I am thinking back too much to the malevolent topiary in Stephen King’s The Shining or, closer to home, the life-imbued bushes of Lucy Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe.

Rounding the corner it is as I suspected might be the case: a locked mesh screen guards the church’s 15th-century porch. Inside, I see a stack of stored fold-up tables; a poster on the sturdy wooden inner door advertises a coffee morning and “Sharpening Solutions” event in three weeks’ time – where parishioners can obtain “quality blade sharpening at affordable prices”. I wander off-piste, around the building’s west, then north side. Poking up out of the straggly grass – it’s been a while since it was mowed – is a lone purple flower, a pyramidal orchid; the boundary of the graveyard is lined by mature horse chestnut trees, though all of their leaves are pockmarked, brown and dying, victims of thousands of tiny, near-invisible leaf-miner moths. Coming back into the open, I notice a mortsafe that, almost gibbet-like, cages a grave.

To keep people out, or its occupant within, I wonder.

It’s disappointing not to have been able to enter the church, as it is one of the few tangible links to the past world of the Rectory – what with so many of the story’s players having preached and worshipped within its whitewashed walls. The place has also, in the Rectory’s absence, taken on something of that notorious house’s mantle, with various anomalous sightings and occurrences reported inside. Before my visit, a close friend regaled me with a vivid childhood memory she recalled from a November Sunday in the early 1970s: an outing here with her sister and parents resulted in her experiencing an overwhelming intuition of malevolence and dread – and the strong sense of an unseen presence in the pulpit. The family fled shortly after entering, her physically shaking younger sister having to be led out by the hand. Today, however, in this topiary-adorned country churchyard, I feel nothing of the sort.

It seems a peaceful space to me.

Quiet, apart from the breeze that buffets the sickly conker trees. I am tempted to imagine the birds are being preternaturally silent. But I should know better – it is the middle of a windy July afternoon, never a time alive with birdsong.

What is noticeably odd, however, is the state of the graves of two of the main protagonists in the Rectory legend, the Reverend Harry Bull and his sister Dodie. Both have been vandalised – apparently by ghost hunters wanting a souvenir – their once-tall headstone crosses smashed off, leaving them unfinished and bereft. Above Harry’s final resting place it also appears as if someone has dug down and removed some of the soil, though perhaps (if I am being generous) a deer might have been responsible.

I find a clue on the nearby noticeboard: a fluorescent green sign warns that CCTV is in operation and that the police have the power to intervene and question anyone in the vicinity.

“Access is not permitted after sundown,” it states ominously.

Later, I learn that drug dealers apparently operate in the churchyard after dark, claiming to be ghost hunters if their presence is questioned by police. And in a scene that could be straight out of The Wicker Man, visiting couples have been known, supposedly, to fornicate on top of the graves. It’s little wonder the surroundings have such a feeling of unfriendliness, and explains why there are so many signs warning that gardens are private, or that security cameras are in operation.

Clearly, I realise, I’m not going to get a fond welcome if I knock on the door of Rectory Cottage.

Instead, I head east along the boundary of the Rectory’s former garden, parallel to the so-called Nun’s Walk where the grey-clad figure was said to stroll. Two concrete griffins gaze out from a neighbouring wall, impassive guardians which remind me of the stone lions Eleanor sees on her fateful journey to that other afflicted abode, in The Haunting of Hill House. I look out across the corner of lawn that lies behind the closed gate.

Nothing. Just a pied wagtail, fluttering in monochrome.

But I am not disappointed, I didn’t expect anything more. Borley, with its phantom rectory, remains a haunted place.

And whatever might walk here, walks alone.