My father was afflicted with an acute fear of heights.

My father was afflicted with an acute fear of heights.

As we lived in the Lincolnshire Fens – the flattest part of the country – this was not ordinarily a concern. Once, on a weekend day trip to the coastal resort of Skegness (I hope the weather lived up to the town’s slogan and was suitably bracing) when I was small – five or six, I’d guess – he decided to take me on one of those chairlift amusement rides; I can’t say whether this was a spontaneous act of bravado on his part, or whether I begged him to go, though I suspect the latter.

We had to stand in front of a chalked line as the bench-seat swung up behind us – Dad was clasping my hand tightly – then quickly collapse ourselves onto the yellow plastic while he fumbled down the metal bar that fitted above our laps. I am reasonably certain that the route of the ride was a long straight line that looped and doubled back on itself along a parallel return cable. At least for one stretch, I think, it went out over the grey sea, though I may be imagining this. Certainly, I have a memory of looking down at my nonchalantly kicking legs, watching the distant brown waves break beneath my shorts-clad knees. Dad kept telling me to stop wriggling about, an odd note in his voice, urging me to sit back and keep hold of the bar. I thought it was great and was oblivious to the panic I can now see he was afflicted by. These terrors were partly a reaction to his own phobia, but mainly, as he told me later, because he was convinced that I would slide underneath the safety bar and drop off the bench into the waters below.

The other time Dad’s fear manifested itself was when we were on holiday. Certain routes took on a foreboding mystique in his head, so that he was loathe, for example, to drive along the dreaded Wrynose Pass when we visited the Lake District, or descend Exmoor’s mighty Porlock Hill. I, in contrast, used to love steep, winding little lanes, and on later holidays when I’d graduated to map-reading duties would deliberately send us along the atlas’ chevron-marked roads; I couldn’t empathise with why he felt uncomfortable driving alongside a vertiginous incline, or why he watched my brother and me scrabbling about on some acutely angled mountainside with a worried expression and shouted warnings urging us away from the edge.

I understand now, because I have become like him.

I find myself telling my nieces to stand well back from the lip of the cliff when we are on a walk along the Dorset coast, or nervously asking them not to move about after they persuade me against my better judgement to go on a Ferris wheel; this condition is one of the few things I can be certain my father and I both share. It started in my teens, a growing sense of unease when faced with a precipitous drop, where before there was none. If I’m enclosed I am fine – it’s the fall that holds the fear, not the height itself. Some of this dread stems from the inevitable thought that enters my head when faced with all that space below: what if I were to jump, what if I were to let my body plummet into the nothing? Should I do it? I wonder sometimes whether this is a Fenlander’s condition, whether the flatness I was born into is somehow encoded inside my very cells, replicating and spreading as I get older, so that one day even looking out of a second-storey window will be too much, forcing me to live out my days anchored down in some bland bungalow among those sterile plains in which I grew up. God, I hope not.

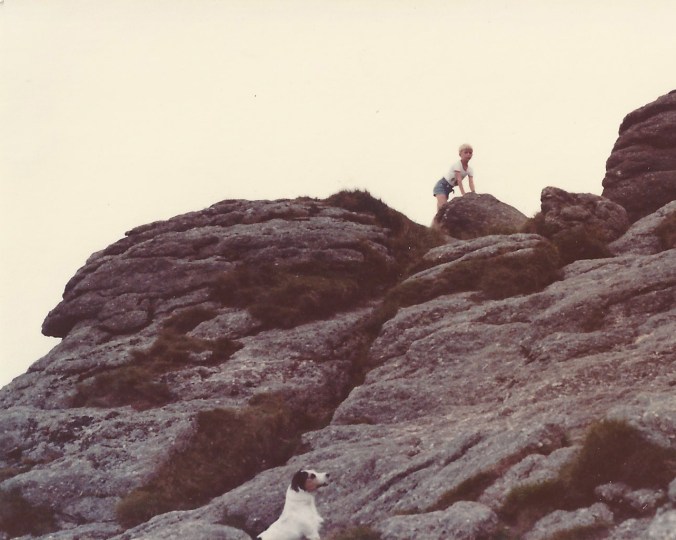

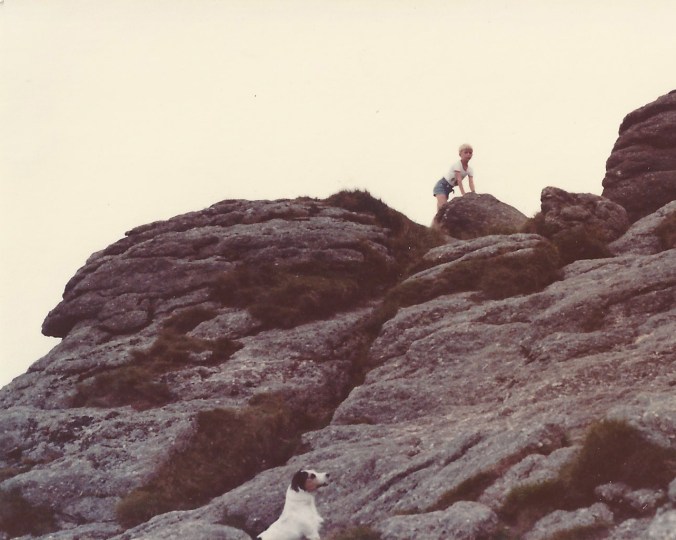

I thought about my father a lot during the writing of Ghostland, particularly when (during September 2017) I went back for the first time to the site of one of my most fondly remembered childhood holidays and revisited the rocky outcrops of Haytor, high on Dartmoor’s eastern flank. Here years before, around its rounded granite reminders of the last ice age, I’d climbed and played with my brother while Dad nervously photographed our exploits. Today the hill itself, though not especially big at a fraction below fifteen hundred feet, seems more than tall enough to my unfit lungs and legs as I trudge up from the visitor centre where fifteen minutes before a German man had rushed inside with a look of existential terror on his face that dissipated in an instant when he was reunited with the bag he’d mislaid full of fifty-pound notes and all of his travel documents. Halfway up, two men in their sixties are attempting to frame themselves in a portrait in which they appear to prop up the still-distant tor with their outstretched palms.

I thought about my father a lot during the writing of Ghostland, particularly when (during September 2017) I went back for the first time to the site of one of my most fondly remembered childhood holidays and revisited the rocky outcrops of Haytor, high on Dartmoor’s eastern flank. Here years before, around its rounded granite reminders of the last ice age, I’d climbed and played with my brother while Dad nervously photographed our exploits. Today the hill itself, though not especially big at a fraction below fifteen hundred feet, seems more than tall enough to my unfit lungs and legs as I trudge up from the visitor centre where fifteen minutes before a German man had rushed inside with a look of existential terror on his face that dissipated in an instant when he was reunited with the bag he’d mislaid full of fifty-pound notes and all of his travel documents. Halfway up, two men in their sixties are attempting to frame themselves in a portrait in which they appear to prop up the still-distant tor with their outstretched palms.

“Dunno how that one will work – it’s dark,” I overhear one say, as I pause to regain my breath.

Rested sufficiently to carry on, I make it to the brow of the hill. There, spread below, is the almost-identical overexposed vista that peers out from my remnant collection of photos and slides. Low cloud moves over the moor, shifting in patches to reveal fleeting features beneath – dank-looking ponds and mires, a loafing herd of cattle sheltering between gorse bushes, and a jumble of oddly shaped rocks – a dreamlike effect that seems like something straight out of a Powell and Pressburger film. The wind’s noise has a rumbling quality that is counterpointed by the high-pitched calls of a pair of meadow pipits, small brown-streaked songbirds that pick neatly around the desiccated cowpats in front of me for insects. It’s surprisingly busy and international up here, with unlikely clusters of people meandering around: an English woman in her seventies, presumably the grandmother, accompanied by two teenage Australian girls and her Jack Russell terrier; a group of four late-middle-aged Americans discussing whether they should visit Castle Drogo next; and a couple of local colleagues having a debate as to whether they perform a “high-skill” occupation – I try to work out what it is they do, but can come to no conclusion.

Now I’ve reached the more impressive lower outcrop – from the road it looks like the protruding sloped spine of some giant extinct animal, though viewed from behind it is a more uniform monolith – I decide I might as well attempt to recreate the ascent I made a lifetime ago, my own underwhelming version of conquering Everest. The rock’s surface is smooth and well-worn, and at first it’s not entirely obvious how the people taking selfies on the summit have made it up there. I watch one of them descend and realise there’s an ill-defined path in the granite – boot-rounded steps that were cut during the middle of the nineteenth century, once accompanied by a handrail that used to guide inadequate rock-climbers like myself to the top, before it rusted to nothing and was finally removed in the 1960s. Mid-way up I have to decide whether to jump across a two-foot chasm – not quite as dramatic as it sounds – in order to tackle the final climb. My uncomfortableness around heights is overtaking me: the space stretching vertically below appears huge, even though the drop cannot be more than three or four feet. The two Australian girls have gone on ahead of their grandmother, who stands at the base taking photos on her phone, when the terrier appears from nowhere and brushes past my stock-still form – his stumpy legs attempt the leap, only for his claws to lose their grip as he touches down, bouncing him into the crevasse. The girls squeal and I expect the worst but the terrier twists in mid-air and corrects his tumble, running off to his waiting mistress as if he had planned the acrobatics all along. Unnerved by the dog’s failed effort I follow suit and jump, my landing ungainly but safe against the lichen-pocked granite, from where it is an easy final ascent up the polished incline.

In an odd coincidence, one of the photos Dad took of me climbing up the Haytor rocks a quarter of a century before shows a similar Jack Russell gazing longingly up at the summit from the bottom of the frame.

I am on top of the world, though when I peer over the edge that familiar urge to let myself fall flickers inside my head. I think back to the chair-lift over the fringe of the North Sea and realise that my father would have been in his forties when we undertook that airborne trip above the swirling breakers – an age I myself have now reached. This seems scarcely credible as I stand here.

Because for me he is immobilised in a series of moments – sitting next to me on that funfair ride, singing one of his various made-up ditties, or throwing his programme to the floor in exasperation as we watch our football team concede yet another inevitable late equaliser (“We always bloody do that!”) – in which he appears as a kind of middle-aged hologram, with a young version of myself flickering beside him for a few all-too-brief seconds. I search my memory for the reassuring grip of his hand around mine, though find only a vague recollection of his grain-tinged face grinning up at me from an old slide, one of his famous self-timer portraits where he propped the camera against a nearby surface and dashed round behind the two of us just in time for the shutter’s release.

Because for me he is immobilised in a series of moments – sitting next to me on that funfair ride, singing one of his various made-up ditties, or throwing his programme to the floor in exasperation as we watch our football team concede yet another inevitable late equaliser (“We always bloody do that!”) – in which he appears as a kind of middle-aged hologram, with a young version of myself flickering beside him for a few all-too-brief seconds. I search my memory for the reassuring grip of his hand around mine, though find only a vague recollection of his grain-tinged face grinning up at me from an old slide, one of his famous self-timer portraits where he propped the camera against a nearby surface and dashed round behind the two of us just in time for the shutter’s release.

From up here the panorama should be spectacular, but the fast-moving cloud remains fitful, obscuring more meaningful views except for a few momentary revelations. It is an odd impression, and I think I can almost make out white-capped waves way down in one of the valleys as an eddy of ashen air drifts past. My heightened angle, at least, better shows the geology of the nearby ridge of boulders that breaches the short distance across to the higher of the tor’s two outcrops. During the shooting of MGM’s 1953 CinemaScope epic Knights of the Round Table – starring Ava Gardner as Guinevere and Robert Taylor as her lover Lancelot – the miniature plain just below me, on which the façade of a castle was built, formed the backdrop to the film’s climactic joust and subsequent broadsword tussle-to-the-death between Lancelot and Modred.

From up here the panorama should be spectacular, but the fast-moving cloud remains fitful, obscuring more meaningful views except for a few momentary revelations. It is an odd impression, and I think I can almost make out white-capped waves way down in one of the valleys as an eddy of ashen air drifts past. My heightened angle, at least, better shows the geology of the nearby ridge of boulders that breaches the short distance across to the higher of the tor’s two outcrops. During the shooting of MGM’s 1953 CinemaScope epic Knights of the Round Table – starring Ava Gardner as Guinevere and Robert Taylor as her lover Lancelot – the miniature plain just below me, on which the façade of a castle was built, formed the backdrop to the film’s climactic joust and subsequent broadsword tussle-to-the-death between Lancelot and Modred.

Descending the tor’s summit is harder than going up, the return leap across the crevasse more tricky, but I make it intact – despite visions of bone-protruding compound fractures and an inelegant helicopter airlift to Torquay hospital, or at best a badly turned ankle – thanks to the proffered hand of a man waiting to ascend. At the base of the monolith the Australian girls are re-telling the dog’s exploits to their grandmother – “He nearly died!” – and as I go down the gorse-strewn path the mist, miraculously, is beginning to clear so that in the distance the real sea, the English Channel, is now visible, and everything in the world seems good.

My father was afflicted with an acute fear of heights.

My father was afflicted with an acute fear of heights.  I thought about my father a lot during the writing of Ghostland, particularly when (during September 2017) I went back for the first time to the site of one of my most fondly remembered childhood holidays and revisited the rocky outcrops of Haytor, high on Dartmoor’s eastern flank. Here years before, around its rounded granite reminders of the last ice age, I’d climbed and played with my brother while Dad nervously photographed our exploits. Today the hill itself, though not especially big at a fraction below fifteen hundred feet, seems more than tall enough to my unfit lungs and legs as I trudge up from the visitor centre where fifteen minutes before a German man had rushed inside with a look of existential terror on his face that dissipated in an instant when he was reunited with the bag he’d mislaid full of fifty-pound notes and all of his travel documents. Halfway up, two men in their sixties are attempting to frame themselves in a portrait in which they appear to prop up the still-distant tor with their outstretched palms.

I thought about my father a lot during the writing of Ghostland, particularly when (during September 2017) I went back for the first time to the site of one of my most fondly remembered childhood holidays and revisited the rocky outcrops of Haytor, high on Dartmoor’s eastern flank. Here years before, around its rounded granite reminders of the last ice age, I’d climbed and played with my brother while Dad nervously photographed our exploits. Today the hill itself, though not especially big at a fraction below fifteen hundred feet, seems more than tall enough to my unfit lungs and legs as I trudge up from the visitor centre where fifteen minutes before a German man had rushed inside with a look of existential terror on his face that dissipated in an instant when he was reunited with the bag he’d mislaid full of fifty-pound notes and all of his travel documents. Halfway up, two men in their sixties are attempting to frame themselves in a portrait in which they appear to prop up the still-distant tor with their outstretched palms.

Because for me he is immobilised in a series of moments – sitting next to me on that funfair ride, singing one of his various made-up ditties, or throwing his programme to the floor in exasperation as we watch our football team concede yet another inevitable late equaliser (“We always bloody do that!”) – in which he appears as a kind of middle-aged hologram, with a young version of myself flickering beside him for a few all-too-brief seconds. I search my memory for the reassuring grip of his hand around mine, though find only a vague recollection of his grain-tinged face grinning up at me from an old slide, one of his famous self-timer portraits where he propped the camera against a nearby surface and dashed round behind the two of us just in time for the shutter’s release.

Because for me he is immobilised in a series of moments – sitting next to me on that funfair ride, singing one of his various made-up ditties, or throwing his programme to the floor in exasperation as we watch our football team concede yet another inevitable late equaliser (“We always bloody do that!”) – in which he appears as a kind of middle-aged hologram, with a young version of myself flickering beside him for a few all-too-brief seconds. I search my memory for the reassuring grip of his hand around mine, though find only a vague recollection of his grain-tinged face grinning up at me from an old slide, one of his famous self-timer portraits where he propped the camera against a nearby surface and dashed round behind the two of us just in time for the shutter’s release. From up here the panorama should be spectacular, but the fast-moving cloud remains fitful, obscuring more meaningful views except for a few momentary revelations. It is an odd impression, and I think I can almost make out white-capped waves way down in one of the valleys as an eddy of ashen air drifts past. My heightened angle, at least, better shows the geology of the nearby ridge of boulders that breaches the short distance across to the higher of the tor’s two outcrops. During the shooting of MGM’s 1953 CinemaScope epic

From up here the panorama should be spectacular, but the fast-moving cloud remains fitful, obscuring more meaningful views except for a few momentary revelations. It is an odd impression, and I think I can almost make out white-capped waves way down in one of the valleys as an eddy of ashen air drifts past. My heightened angle, at least, better shows the geology of the nearby ridge of boulders that breaches the short distance across to the higher of the tor’s two outcrops. During the shooting of MGM’s 1953 CinemaScope epic